In the new normal, our cities will need to reconsider the relationship between buildings and infrastructure.

‘Cities are a process’: Manuel Castells 1996.

London, more than many cities has embraced this mantra, continually evolving in response to the demands of a working metropolis, adapting to new technology and re-inventing itself in the wake of cataclysmic events, including Covid-19.

For our urban environment to remain healthy, the interdependencies between buildings and infrastructure must also evolve: London’s skyline may be defined by its architecture, but its lifeblood is defined by ease and efficiency of movement.

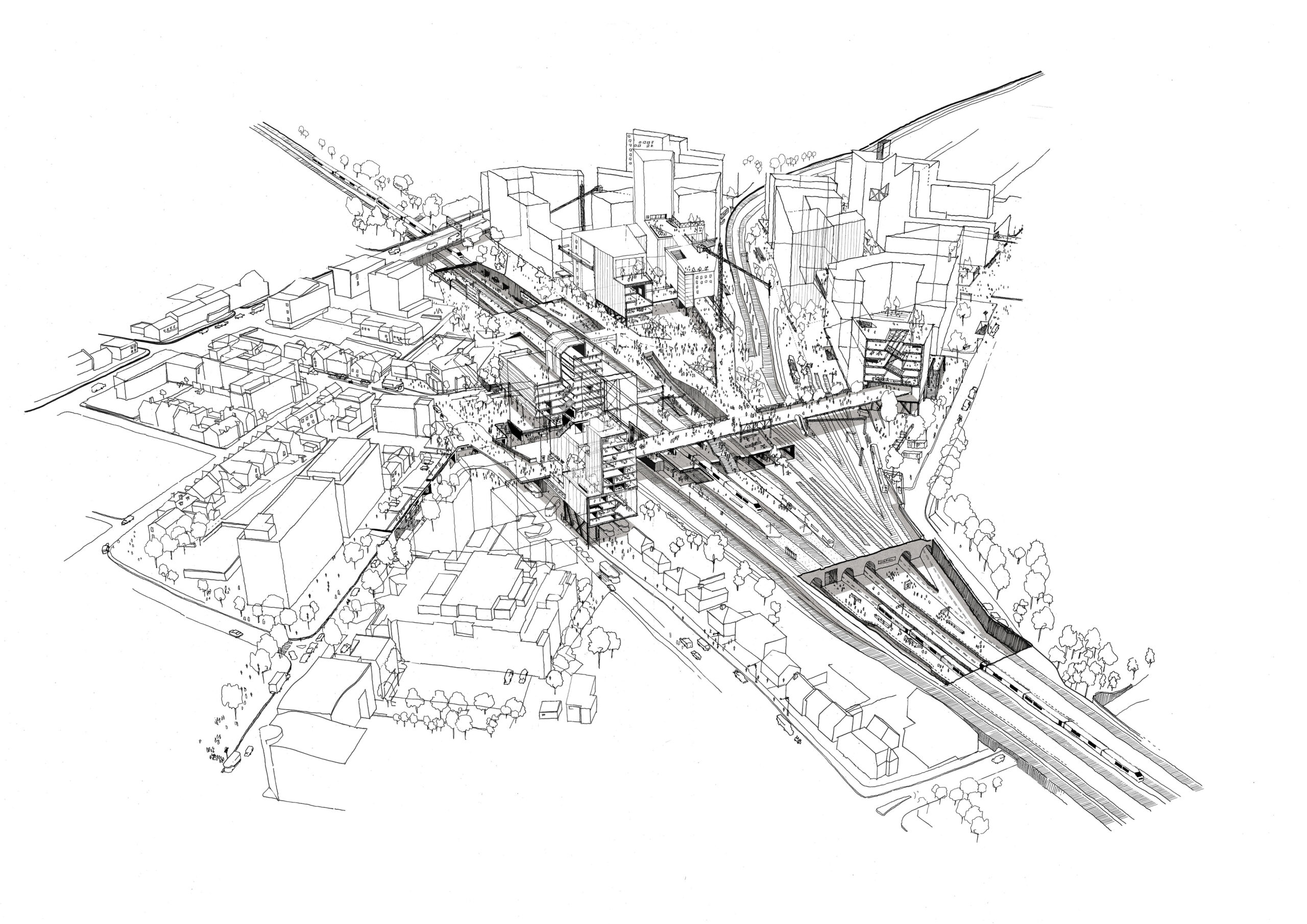

Railway City – a proposal for a new vertical living, working and shopping hub to invigorate London’s satellite locations with high density transport focused urban centres.

During the 20th and early 21st centuries, architectural movements have placed experiments with this interdependence at the forefront of proposals for a contemporary urban schema. Le Corbusier’s ‘City of Tomorrow’ centred on the idea that the scale and speed of infrastructure necessary for modern urban life was incompatible with the world of the pedestrian. By manipulating the city section, Le Corbusier was able to separate the pedestrian and the car – a radically different way of seeing the city and experimenting with previously unimagined levels of density.

Subsequent architectural movements, such as Japan’s Metabolists, spearheaded by Fumihiko Maki and Kenzo Tange experimented with vast ‘collective forms’ or megastructures that combined infrastructure, leisure, living and working under a single roof, an approach to urbanism that has become de-rigueur in the colossal eruption of building that has blanketed Asia in recent years and which has influenced the urban planning solutions we now find in London.

Mobility and density are at the heart of these urban developments and, until 2020, there was little reason to believe that cities wouldn’t become increasingly dense with highly mobile populations. But, for the time being, we have had to pause and learn to stay still. For how long we cannot be sure, though it is certain that things won’t ever return to the way they were.

The relationship between architecture and infrastructure needs to adapt again, and we will need to test its resilience to see if it’s ability to aggregate, sort and process are as effective in an era when we need to socially distance as they were in one where we were constantly mobile.

Can these spaces still inspire and delight, or will their evolution rob the city of the sociability and vibrancy that make cities like London such unique, dynamic and desirable places to be? In our efforts to create a lean, sustainable future that truly embraces an evolving urban process, we as architects will need to embrace new ways of designing buildings holistically and posit new ways to interact with the infrastructure of the city.